From the streets of Harlem to the stages of ballet, Dandyism and jazz have fundamentally altered the way we experience beauty, dance, and sartorial self-expression in the United States; with the upcoming opening of the Met Costume Institute’s “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style”, the history, role, and gorgeous looks of Black Dandyism are having a moment.

The Dinner Party. Tyler Mitchell (@tylersphotos) was commissioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (@metmuseum), New York, to document the Costume Institute’s exhibition “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” for the accompanying catalogue.

A moment that was none too prescient—right as government policies erase the histories of the Black and Brown, and the Kennedy Center, our national cultural center, gets rid of its DEI initiatives, one of the (other) foremost cultural institutions: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, lifts the histories, the glamour, and the contributions of Black fashion and identity.

Exhibitions of Superfine’s scale are planned years in advance and I doubt the curators had any idea just HOW relevant and filled with compound resistance the timing of this opening would be.

Fashion and ballet fall solidly into the camps of extremely elitist Eurocentric worlds and industries—or do they?

Elitist, yes. No question.

NYC Ballet even stopped selling their upper-tier “more affordable” seats until enough of the lower level (realistically) $100+ sell. A tax-exempt organization not even pretending to make their work available to a wider public—the laurels upon which they rest are thick and strong.

But if you look just a little closer (or zoom a little further out—as the deep and narrow often reflects the wide and encompassing), you’ll see that Black culture has had a profound influence on the development of both, particularly the American ballet aesthetic.

What is the American ballet aesthetic?

You’ll find plenty of Western European and Russian-trained dancers (and certainly choreographies) on our stages, but the look that is uniquely ours is the Balanchine/NYC Ballet style. With its emphasis on speed, forward-thrusting (jazzy) hips, dynamic musicality, syncopation, and use of the off-balance. Many of these influences are directly from jazz music, dance, and Black dance artists. However, it’s worth noting, neo-classical ballet is decidedly without improvisation—a key tenet in jazz music. It’s still ballet after all—an art form rooted in a mix of royal hierarchy and military academies.

Gonzalo Garcia & Megan Fairchild in “Rubies” Photo: Erin Baiano

The Origins of Black Dandyism

While the term "dandy" traditionally referred to an elegant and often flamboyant man of fashion, Black Dandyism developed as a means of resistance and self-definition. It had its earliest origins in the slave trade—where young African (usually boys) were dressed in ornate clothing serving as status symbols for their “owners.” Then, in post-emancipation America, it was reclaimed. Black individuals used sharp clothing and appearance to assert agency in a society seeking to minimize their humanity. It was a defiant rejection of the "slave" body, and a deliberate assertion of dignity in a world bent on denying it.

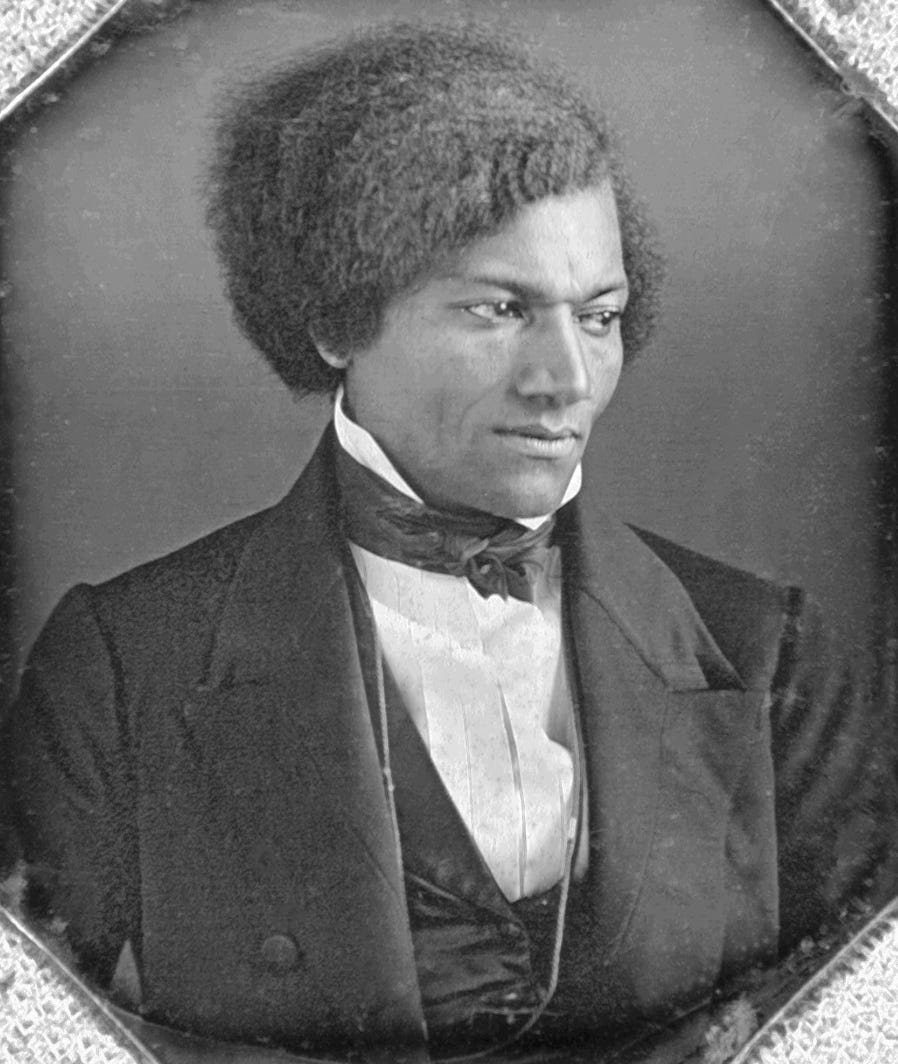

Figures like Frederick Douglass and the "dandy" Beau Brummell—whose fashion was imitated in Black communities—helped solidify the idea that dress could be an expression of personal power. During the Harlem Renaissance, this style came into full bloom, with figures like Langston Hughes and Josephine Baker. Fashion became a medium through which Black Americans could negotiate visibility, status, and political resistance.

The Roots of Jazz and Its Movement Aesthetic

Simultaneously, another revolutionary cultural form was taking root: jazz. Emerging from the African American communities in New Orleans in the early 20th century, jazz was rooted in the experiences and histories of Black Americans, blending West African rhythms, blues, and European musical traditions. Jazz music’s hallmark is its improvisational nature, where musicians engage in spontaneous creation, interpreting the moment in real time.

Jazz wasn’t just a sound, it was an aesthetic that influenced everything from music to fashion to dance. Jazz dance was a natural outgrowth of the music, marked by its grounded, rhythmic quality and freedom of expression. Early jazz dancers like Josephine Baker, and later figures like Katherine Dunham, used the dance floor as a space to inhabit a uniquely American form of movement, free from classical ballet’s constraints. The syncopated rhythms and more open movements of jazz became expressions of Black joy, pain, and resilience, offering a stark contrast to the structured steps of classical ballet.

As ballet continued to evolve in the United States during the 20th century, it was impossible to ignore the influence of jazz. Though ballet initially presented an image of Eurocentric refinement, the rise of American modern (modern in the descriptive sense of the word, not as in the Modern style of Graham/Limón etc.) ballet—led by choreographers like George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins—began to incorporate jazz-inflected rhythms and movements. Think Balanchine’s Rubies, Slaughter on 10th Avenue, or Robbins’ Fancy Free. These choreographies signaled a shift in the American ballet aesthetic to one that was uniquely its own—rather than a European import.

Even when Black bodies were largely excluded from the ballet stage, the syncopated rhythms and improvisational style of jazz music seeped into choreography.

Later artists like the gargantuan Alvin Ailey brought Black dance aesthetics intentionally to the forefront. Ailey’s Revelations, for example, integrated jazz, gospel, and modern dance into a unique style that celebrated Black experiences. His works challenged the notion that dance concerts should be static or removed from the emotional power of Black culture.

The Black Dandy Aesthetic Today

The Black dandy aesthetic, like jazz dance, is not just about individual expression; it’s a language unto itself. The careful lines of a well-tailored suit, the sharp elegance of a top hat, are their own vocabulary.

Today, the influence of Black Dandyism and jazz continues to inform fashion and performance, as seen in designers like Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss, whose work reflects a deep understanding of Black cultural heritage and its intersection with modern aesthetics. Or think of the work of dancers like Lil Buck, who embody the fluidity between classical ballet, jazz, and the movement traditions passed down from Black culture.

The enduring legacy of Black culture is such that even when it is consciously erased or marginalized—it lives—on our stages, in and on our bodies. The upcoming exhibition: “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” holds this history up in conscious, glamorous light.

Cynthia Dragoni April 2025

Share this post